Sweetness is about to be the subject of a bitter courtroom fight.

Sweetness is about to be the subject of a bitter courtroom fight.

In one corner is the artificial sweetener in the blue packet, Equal; in the other is its best-selling rival in the yellow packet, Splenda.

The maker of Equal contends that Splenda has been misleading millions of consumers by fostering the notion, through television and print advertising, that Splenda is made from sugar and is natural. Splenda’s maker counters that the process to make the sweetener does indeed start with sugar.Next Monday, a lawsuit brought by the maker of Equal, Merisant, against Splenda’s maker, McNeil Nutritionals, is scheduled to go before a jury in Federal District Court in Philadelphia.

At stake is leadership of the fiercely competitive $1.5 billion artificial sweetener market. Equal had once dominated the market, finding its way into more than 6,000 consumer products like Diet Coke and Diet Pepsi, the two biggest buyers of artificial sweeteners in the world.

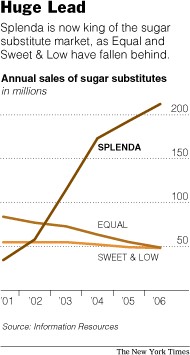

But since Splenda was introduced in late 1999, Equal has steadily been elbowed aside and Splenda is now No. 1, with 62 percent of the market in the United States.

It is unusual for a dispute over advertising claims to go to a jury trial. The case centers on Splenda’s tagline “Made from sugar, so it tastes like sugar” — a claim that Equal mocks as an “urban myth” on its Web site.

While both sides are expected to present phalanxes of neurobiologists and chemists as expert witnesses, the dispute hinges on the role of language in creating and defining the product.

“The phrase ‘made from sugar’ may seem simple enough, but it has spawned an epic battle among the parties over proper diction and syntax,” the judge overseeing the case, Gene E. K. Pratter, wrote in an opinion last month.

“For example, McNeil claims that ‘made from sugar’ clearly excludes the interpretation that Splenda is sugar, or that Splenda is made with sugar,” she continued. “Made with sugar would mean that sugar is an ingredient listed on the package. Drawing upon an often effective rhetorical device, McNeil asks the question, how could a consumer interpret a product that is ‘made from sugar’ and ‘tastes like sugar’ as actually being sugar?”

Kevin L. Keller, a marketing professor at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth, said that the language at issue had “a legal perspective, a marketing perspective and a health perspective.”

“The challenge is how do you seek and find the truth in each of these different perspectives,” he said.

Merisant is seeking the disgorgement of at least $176 million in Splenda’s profits as well as court approval to force Splenda’s maker to revamp its advertising and marketing. The jury trial is expected to last two weeks.

Splenda’s core ingredient is a nonnutritive sweetener that does not grow in sugar fields or appear elsewhere naturally. Rather, the core ingredient, sucralose, is manufactured in laboratories as a synthetic compound. Despite its similar-sounding name, sucralose is not the same thing as sucrose, the technical name for pure table sugar.

Splenda’s maker McNeil, a unit of the Johnson & Johnson drug and consumer goods giant, has patented dozens of ways to manufacture sucralose. Some of them are based on sucrose. One is even based on raffinose, a sugar-relative found in beans, onions and broccoli. But others are based on nonsugars — a point that Equal’s maker, prowling through filed patents, has seized upon.

McNeil says that the process it uses to manufacture Splenda starts with sugar, pure and simple. To make sucralose, McNeil adds three chlorine atoms that are naturally found in foods like salt and lettuce to a molecule of sucrose. The sucrose disappears in the manufacturing process, but the result — sucralose — is 600 times as sweet as ordinary table sugar. Splenda then mixes two bulking agents, dextrose and maltodextrin, into the sucralose.

The chemistry is complex, and it may be baffling for a jury to hear about a process that starts out involving sugar but ends up lacking it.

The chemistry is complex, and it may be baffling for a jury to hear about a process that starts out involving sugar but ends up lacking it.

Despite its use of sugar as the starting point for making sucralose, nowhere do the words “sugar” or “sucrose” appear on Splenda’s ingredient list. That is because under Food and Drug Administration regulations, it cannot list a substance that has vaporized during the manufacturing process.

In January 2005, in its answer to the lawsuit filed by Merisant that previous November, McNeil said that “the sweetening ingredient in Splenda is made by a multistep process that starts with cane sugar.” But it then added that “Splenda is an artificial sweetener that does not contain sugar” — presumably because the sugar disappears in the manufacturing process.

In papers that were filed with the court and sealed — but were then cited by the judge in her opinion last month — McNeil acknowledged that “unaltered sugar/sucrose is not an ingredient in Splenda.” Rebecca Tushnet, a professor of advertising law at Georgetown University who has followed the case, said: “The key issue is, what can you say about your product that’s made in a lab and its relationship to nature? How much can you suggest that it’s natural, whether because the components were found in nature, or your body processes it as natural?”

Merisant argues that it is chemistry, not sugar, that generates Splenda’s sweetness. “At the end of the day, they say Splenda is ‘made from sugar,’ ” said Merisant’s lead outside lawyer, Gregory LoCascio of Kirkland & Ellis. “People think it’s sugar without the calories, or skim sugar, or magic sugar, and it’s not. It’s artificial sweetener.”

McNeil’s outside lawyers referred all calls to a McNeil spokeswoman, Julie Keenan, who provided a statement saying that Splenda “is made from pure cane sugar by a patented process that makes three atomic changes to the sugar (sucrose) molecule.”

“The resulting sweetener, called sucralose, retains the sweet taste of sugar,” she said.

Equal, also known as aspartame, also does not have an iota of sugar in it. It is composed of two amino acids and a methyl ester group. But Equal promotes itself as an artificial sweetener and tones down the references to sugar in its marketing, saying only that it “has sweet, clean taste, like sugar.”

Still, Equal has a powerful if unlikely ally in its battle against Splenda: the Sugar Association, a trade and lobbying group for the $10 billion American natural sugar industry. The association has separately sued Splenda’s makers over its claims to be related to sugar.

Legal battles over the authenticity of consumer products are not new. In 1996, the maker of Ragu, Conopco, unsuccessfully sued the maker of Prego, the Campbell Soup Company, over Prego’s claim that its pasta sauce was “thickest.” In another case, Hot Wax unsuccessfully sued Turtle Wax in 1999, contending that it created the impression that its car wax actually contained wax. (It did not.)

Equal was first sold in 1982 by G. D. Searle, which was then acquired by Monsanto. Merisant, a private company in Chicago that describes itself as David to McNeil’s Goliath, bought the Equal part of Monsanto’s business in March 2000. Another brand of aspartame, NutraSweet, is sold by the Nutra-Sweet Company, also in Chicago.

After gaining approval from the F.D.A., McNeil introduced Splenda in late 1999. Because of an aggressive marketing campaign by Alchemy, a New York advertising agency, Splenda immediately began to eat into Equal’s sales. In 2001, Splenda had annual sales of $34 million, compared with Equal’s $84 million, according to Information Resources Inc., a data company.

By late 2004, McNeil had to ration shipments of Splenda amid soaring demand. McNeil has spent over $235 million since then to promote Splenda.

By late 2004, McNeil had to ration shipments of Splenda amid soaring demand. McNeil has spent over $235 million since then to promote Splenda.

In less than a decade, Splenda has come to dominate the American artificial sweetener market. Last year, it had sales of $212 million, dwarfing Equal’s sales of $49 million. Splenda is now not just in packets and bulk, but in Cocoa Puffs, Diet Coke, Pedialyte, and nearly 4,500 other consumer products.

In its court filings, Merisant cites presentations made by Alchemy, Splenda’s advertising agency, that cited “the decision to position Splenda as not artificial.”

In those presentations, the agency says that Splenda should be thought of as “sugar without the calories,” putting “significant distance from “artificial sweeteners.”

For a time in 2002, McNeil added the line “but it’s not sugar.” Sales fizzled.

McNeil dropped the line and went back to “made like sugar, tastes like sugar” and “think sugar, say Splenda.” Sales shot back up.

One apparent reason was that for consumers polled by McNeil, the tagline “made from sugar” caused some to be unclear as to whether Splenda is truly natural, according to a sealed declaration filed by a lawyer for Merisant who saw the documents. The comments were quoted by the judge in her March opinion.

Professor Keller of Dartmouth said that “it’s all going to come down to consumer perceptions, and how they interpret what these claims are, and are they accurate.”

>>>>2007.4.6 The New York Times

>>>>20074/23~29 聯合報《紐約時報精選周報》

留言列表

留言列表